In much of Sardinia they are called cumbessias, in Oristanese muristenes: they are isolated ghost villages with a mystique that is easy to come across when travelling around the island in search of unusual and precious places. Silent all year round, they were inhabited only on the days of the novenas (nine days or weeks of prayers to a saint), amidst devotion, the breaking of vows and cheerful group celebrations in honour of the saints after whom the small country churches, often small jewels of medieval art, are named. The sanctuaries opened their doors day and night to the faithful, while the small houses, with humble facilities, welcomed the pilgrims who arrived in procession on foot or on horseback from the village parish. The prior would start the rituals marked by gosos, ancient and poignant songs of praise sung in chorus at sunrise and sunset, celebrations in church and moments of recollection and reflection during walks around the villages.

It wasn’t just prayers and spirituality, the novenas were also a popular communal feast, with typical dishes being prepared and fires lit for the roasts. After dinner, people stayed for hours together, with poetry competitions, traditional songs and dances, and then slept in the little houses arranged in a circle around the church or in a row like a village street.

The habit of staying and resting in sacred places may have very ancient roots, perhaps Nuragic. As Aristotle also said, in the prehistoric period of Sardinian civilisation, incubation was widespread, a curious ritual that helped to establish contact with the afterlife and the divine, and it was considered a good remedy for the soul and the body to sleep, for short periods and in special circumstances, 'near the heroes', next to the Giants’ tombs.

For some decades now, the tradition of staying in the novenaries scattered throughout Sardinia has slowly been lost. Today, after the religious rites, everyone returns home and the villages remain silent.

But inexorably the ancient tradition emerges and some reopen their doors day and night; sooner or later the sacred festival will return.

May at the sanctuary of Santa Cristina, Paulilatino

Water is the transcendental dimension of Nature; when man dips his toe into the sacred well, he feels its energy and becomes the point of encounter and balance with the cosmic forces of the sky and the primordial power of Mother Earth; it is there that the divine resides.

June at the novenary of San Mauro, Sorgono

An enormous rose window on its façade looks out over the most important group of menhirs in the Mediterranean, and around the church are the muristenes for pilgrims and porticos for merchants offering their wares. The village comes alive three times a year with songs and prayers but the main festival is in June when an exciting palio is held.

September in the village of San Salvatore di Sinis, Cabras

The church has ancient origins, built on a prehistoric sanctuary that later became early Christian. The village sleeps through the year until a great feast of music, dancing and delicious local produce welcomes the arrival from the village of the Corsa degli Scalzi, the 900 barefoot devotees in white robes who revive the ancient ritual of devotion to the saint.

September in the park of Santa Sabina, Silanus

It looks like a scene specially constructed for a photography set: a nuraghe, a small Byzantine church built on even more archaic remains and with stones from the ruined nuraghi, a row of small, delightful pilgrims' cottages and, all around, a valley teeming with prehistoric remains. No doubt about it, this is a place of the heart.

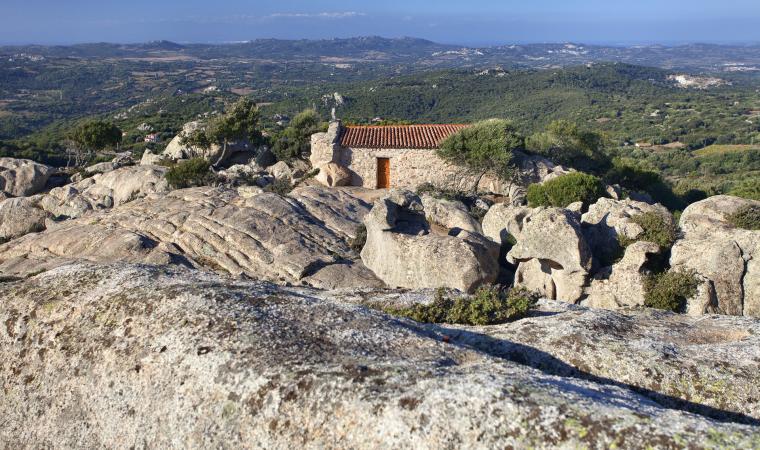

October at the church of San Francesco di Lula

According to an ancient tale, a procession leaves at night to reach the sanctuary at the foot of Mount Albo. The cottages are open to shelter the pilgrims, and the sheep's broth is ready for cooking su filindeu, the golden threads of thin handmade pasta, a typical dish of Barbagia cuisine offered in the name of the saint. In these parts, devotion is always alive.

October at the novenary of San Serafino, Ghilarza

It was once a Roman villa on which a Byzantine church was built, occupied by oriental monks who lived in the small medieval village next door. Abandoned over time, it has now been resurrected as muristenes, which open their doors during the novenas. Music and dancing break the silence, awaiting the visit of the simulacrum brought from house to house, amidst sacred songs and offerings of good food.