Porto Paglia - Marina di Gonnesa

A wonderful oasis ideal for all tastes, from those who love relaxing in nature and romantic atmospheres to sea sports enthusiasts. The marina of Gonnesa is an enchanting, endless expanse of soft, firm sand with a beautiful golden-amber colour within the Golfo del Leone (or of Gonnesa). The beach is wide and three and a half kilometres long, offering picture postcard views: fossil dunes covered with Mediterranean greenery and the surrounding landscape of colours ranging from beige to reddish, contrasting with the white sand and the iridescent sea with its shades of emerald green and blue. Although the sandy expanse is unique and seamless, you will hear talk of ‘beaches’ - in fact, there are four parts, corresponding to the same number of access points to the beach. Each stretch is beautiful and is identified as a beach in itself, with its own name and its own distinctive features: Porto Paglia, Punta s’Arena, Plag’e mesu and Funtanamare.

The southernmost part of the marina is Porto Paglia, which gets its name from the ancient tuna fishery dating back to the 18th century and, for two centuries, one of the most productive in the Mediterranean. The impressive complex formed by the dwellings of the tuna fishermen and the dock, which was renovated and used as a tourist village at the end of the twentieth century, dominates the promontory south of the gulf

. The beach is about half a kilometre long and has light sand with hints of gold and pink streaks due to the minerals mixed in with it. Scattered here and there on the shoreline, you will see trachyte rocks. The seabed is sandy for long stretches, then it gets deeper with pebbles. Currents and winds often agitate the clear waters, so the beach is much loved by kite and wind surf enthusiasts in search of waves.

Porto Paglia, the ‘pearl’ of Gonnesa, is the boundary between the Iglesiente and Sulcis coasts, where the elevations extend to the sea, with green limestone cliffs. The sandy shore is preceded by a stretch of wild coastline, with pebbly coves framed by trachyte rock faces overlooking the sea, similar to those of the Island of San Pietro and once crossed by the railway line that connected the Iglesiente mines to Portovesme. Right here, at the southernmost tip of the beach, highly appreciated by those who go underwater fishing and diving, the chiesetta della tonnara (little church of the tuna fishery), which was built directly on the rocks, stands out in a surreal context. A short walk on the rocky outcrops will take you to it at low tide. It is the only one in Sardinia that can be accessed directly from the sea: boats can be anchored at the small quay of the churchyard. Along the path, you will also see the ruins of a tower built under Spanish dominion to defend the southwestern coasts from pirate raids. In addition, hawks nest in the sandstone ravines surrounding the beach. On a beach suited to people who love relaxation and unspoiled nature, there is no shortage of services: you will find refreshment areas and bathing establishments directly on the beach, where you can rent beach umbrellas and sun loungers.

Plag’e mesu, or ‘middle beach’, as the name implies, is the central stretch of beach in the gulf, a huge strip of fine, golden sand, which is never crowded, even at the height of summer. The northernmost beach is Fontanamare, delimited by cliffs and by the ruins of the mining port. Here, you can admire the dunes of Gonnesa, shaped by the northwesterly wind, making it one of the Sardinian coastal stretches most frequented by surfers. Just beyond the gulf, the limestone rock known as Pan di Zucchero stands out and is the tallest rock in Europe, rising majestically out of the water. Close to the beach you can relax in a pine forest, alongside the marsh of sa Masa, where rare aquatic birds dwell, among which the western swamphen, and is a paradise for birdwatching enthusiasts.

From Iglesias and Gonnesa, you can reach the marina by first taking state road SS 126 and then scenic route 108 towards Portoscuso, along which you will find a detour taking you to the village of Porto Paglia. From the large car park, you can get to the beach via a flight of steps.

Funtanamare

A four-kilometre stretch of soft, firm sand, divided into four sections with four access points: Porto Paglia, Punt’e s’Arena, Plag’e mesu and Funtanamare. The Marina di Gonnesa is one of the largest, most enchanting and well-equipped shorelines along the Sulcis and Iglesiente coast, the border between the two territories on the southwestern extremity of the island. It extends within the captivating Golfo del Leone, bordered to the south by the eighteenth-century tuna fishery of Porto Paglia and to the north by the mining village of Funtanamare. The bay is framed by the elevations of the Sulcis region, with their lush offshoots reaching down to the sea, creating a marvellous series of golden sandy shorelines and limestone cliffs. There is a lush, green pine forest next to the beach. A little further on, you’ll find the sa Masa marshland, a destination for birdwatching enthusiasts, inhabited by rare aquatic birds, such as the western swamphen and the marbled duck.

The northernmost and largest part of the Gonnesa coast is Funtan’e Mari (in Campidano dialect): it’s about three kilometres long and is wild and evocative of the mining activities of the past. The fine sand is golden and pink in colour; the splendid multicoloured sea ranges from emerald green to blue; the waters are shallow and the seabed is sandy for a long stretch, becoming pebbly. Without the shelter of rocks for a few hundred metres and exposed to winds and currents, it is a year-round paradise for windsurfing and kitesurfing enthusiasts, who seek the waves generated by the northwesterly wind, and those who enjoy underwater fishing and diving also appreciate it. Funtanamare is very crowded in the summer but it’s also popular in the winter: many people go there for walks to admire the force of the sea and the spectacular views, especially at sunset, when you can see the outline of the Pan di Zucchero (meaning sugarloaf) sea stack and the Masua promontories overlooking the sea.

There is parking next to the beach, a restaurant nearby and a refreshment area right on the beach. The sandy coastline is framed by a border of fossil dunes covered in lush vegetation, limestone cliffs and the ruins of the 19th-century mining port. The town was once involved in mining activities, as you will see from the mining structures and facilities: the mineral loads were brought to the beach and placed onto small boats, the bilancelle (small Sardinian boats with lateens), which transported them to the island of San Pietro. You will also notice the mouth of a drainage tunnel from 1875, known by the name of Umberto I. There are also ruins of military fortifications from the Second World War.

Although Gonnesa, nestled at the foot of Mount Uda, is not a coastal town, it is only two kilometres from the sea. The southernmost stretch of its coast is Porto Paglia, followed by Punta s’Arena and Plag’e mesu, the ‘middle beach’ that connects the southern part to Funtanamare. You can reach the coast by taking state road SS 126 and provincial road SP 83 and passing through mining landscapes in Iglesias, between abandoned facilities in Monteponi and ‘red mountains’. Then, travelling from Gonnesa to Portoscuso, along the ‘scenic’ road 108, you will see small and enchanting coves with a view of the nearby islands of Sant’Antioco and San Pietro.

Gonnesa was also a protagonist during the historic mining period: various abandoned sites are evidence of this, including the village of Normann, with its mine close to the Cave of Santa Barbara, an unspoilt jewel of nature. In addition to the remains of industrial archaeology, the area is dotted with prehistoric sites, particularly the village of Seruci, the most important Nuragic complex in Sulcis, consisting of a complex nuraghe, a turreted defence wall, a Giants’ Tomb and a village of over a hundred huts.

Calich lagoon

It is a ‘buffer zone’ between land and sea, with shallow, calm waters and it is shaped like a ‘goblet’ - hence the name. It is also a vital ‘lung’ where native plants grow and numerous varieties of fish and rare aquatic birds live. The Calich lagoon (or pond) is an integral part of the Porto Conte park and is one of the most significant nature sites on the Riviera del Corallo and in the whole of Nurra, a historical territory in the north-west of the island. Its waters, on average just over a metre deep, extend over a surface area of 97 hectares and a length of two and a half kilometres, running parallel to the coast of Alghero, which is an average of 400 metres away. Towards the sea, a strip of sand runs alongside it, with fossil or ‘living’ dunes, like those of the beautiful beach of Maria Pia.

The Calich occupies the area next to the northern outskirts of the Catalan town, a stretch that runs from the tip of the Gall, near the Alghero district of Fertilia, as far as the locality of San Giovanni, a few minutes’ drive from the historic centre. The wetland area communicates with the sea through the large canal of Fertilia, 60 metres wide and two metres deep - the deepest part of the pond -, accommodating the harbour of the small village, the original settlement of which was exactly the Calich village. Where it overlooks the sea, the lagoon is dominated by the ruins of a bridge dating back to the Roman era, later rebuilt in the Middle Ages. Ten of its 24 original arches were demolished in the 1930s during the reclamation of the then malarial territory. The opening to the sea that transformed the pond into a lagoon also dates back to that time. Its current form is the result of other works, such as dredging and building of canals.

The lagoon-pond is divided into two sectors: the true Calich that runs from the western extremity to the mouth of the Barca rivulet, its main tributary, and the Calighet (little Calich), from the mouth of the rivulet to the southeastern extremity: it represents the slender ’stem’ of its goblet shape. Together, they form a salt water wetland in between the ‘areas of botanical interest for the protection of floristic biodiversity’, an ecosystem that includes over 350 plant species divided into 60 families, with multiple endemic species. The vegetation varies according to the salinity of the water: you will see halophyte plants, in particular glasswort, along the banks, while as you move away from the edge of the lagoon, you will see herbaceous plants and perennial shrubs, such as sea rushes. Deeper inside, you will find lemon, helichrysum, spurge, thymelea and centaurea horrida. When the wind blows, you will hear a myriad of rattling plants.

The pond, a bird protection oasis, is home to egrets, grey herons, ospreys and marsh harriers, ducks, black-winged stilts, cormorants, pink flamingos with their regal plumage, little terns and mallards, kingfishers, western swamphens and little grebes, some of which stop here to spend the winter, mate and nest. In short, this is an ideal destination for birdwatching lovers and it also offers shelter and food to numerous fish. Unsurprisingly, it is also a fish-farm, where eels, grey mullet, crabs, flathead mullet, gilthead bream, seabream, sole and sea bass are bred (and fished). As part of the regional protection programme, the footpaths have been modernised and a bivalve mollusc breeding station has been added, handled by the Porto Conte park. In the adjacent protected area, you will discover other natural attractions: the pinewood of s’Arenosu, the forest of Le Prigionette, mounts Doglia and Timidone and the marine area of Capo Caccia, a destination for boat trips, with Punta Giglio, the island of Foraddada, the beach of Mugoni and, above all, Neptune’s grotto. The park is also an open air museum, where the nuraghe Palmavera and the ruins of the Roman villa of Sant’Imbenia stand out. The beach adjacent to the Calich is Maria Pia and the city coastline of Lido di San Giovanni is nearby, while Le Bombarde and the Lazzaretto are two kilometres further north. After so much nature, sea and archaeology, you can relax in the historic centre of Alghero, known as ‘Barceloneta’, because of its Catalan origins (of which there are still traces).

Valley of Lanaitto

The most accessible ‘gateway’ to the rugged Supramonte elevations, famous for its intricate pathways, once known only to shepherds and coal merchants, now trekking trails that lead to natural and archaeological treasures. The valley of Lanaitto (also spelled Lanaitho or Lanaittu) is in a setting of spellbinding scenery in the territories of Oliena and Dorgali, amidst imposing limestone ridges that have generated sinkholes, canyons, aiguilles and caves. It would be a lunar landscape if it were not covered in lush woodland in a thousand shades of green: holm oaks, terebinths, maples, olive trees and centuries-old junipers embrace winding dirt paths. The silence is only broken by the rustling of leaves. In amidst the natural monuments, prehistoric sites and pinnettos - shepherds’ retreats that have become shelters for trekkers - it is easy to spot mouflons or see eagles flying. Bring your hiking shoes, backpack and water bottle and don't forget your smartphone and binoculars.

Starting from Oliena, after crossing the bridge over Lake Cedrino, the spring of su Gologone is the first spectacular stop on the excursion to Lanaitto, just before the entrance to the valley: crystal clear waters gush from a deep rift, carved for kilometres out of the white rocks, over thousands of years. All around, the shade of the eucalyptus, oleander and willow trees is perfect for picnics and relaxing. After leaving this idyllic place and parking your car next to a shelter, you will walk down to a green basin guarded by walls known to climbers: in front of you is the limestone backdrop of Monte Corrasi, behind which there are the basalt columns of the Gollei plateau, a ‘Gothic cathedral’ created by nature. A tree-lined path leads to the entrances of the caves of sa Oche and su Bentu, which are connected to each other and among the longest in Europe, true havens for speleologists. Inside them, karst phenomena have created tunnels that are kilometres long, rooms that are up to one hundred metres high, decorated with stalactites and stalagmites, floors covered with sharp crystals, underground lakes and sandy beaches. Sa Oche means ‘the voice’ and, in reality, a roar resounds from within, during heavy rains, when the water flows out, flooding the valley. The same impetuous underground torrent has carved su Bentu (the wind), which has been the ‘stage’ of survival courses for astronauts several times. Inside, nature has created a fairy tale: there are concretions that look like prehistoric animals, eccentric ones extending in every direction, limestone curtains of all colours, basins of extraordinarily transparent water.

At Lanaitto, the caves are witnesses of the first homo sapiens on the Island. In the grotta Corbeddu, just south of the other two caves, human bones dating back to between seven and thirteen thousand years ago were found, as well as traces of animals that are now extinct. The cavern, habitat of unique micro-organisms and embellished by stalactites and stalagmites, was the secret refuge of the gentleman bandit Giovanni Corbeddu Salis while he was on the run (1880-1898). It is said that this ‘king of the scrub’ stole from the rich to give to the needy and had set up a ‘court’ inside the cave, where suspects were only judged with clear evidence of their guilt. After leaving the cave, walking along continuous uphill and downhill stretches leading to the valley floor, you will reach the late-Nuragic village of sa Sedda ‘e sos Carros, used as a parking area in the past for wagons transporting timber. Its huts surround a sacred well made of light limestone and dark basalt rocks, unique in the Mediterranean. The water gushed from nine mouflon heads carved in the stone and collected in a circular stepped pool, possibly used for rituals.

The last stage of the tour of the valley - to which a whole day should be dedicated - is Monte Tiscali. A Nuragic village hides on its summit, which can be accessed via a very narrow crevice in the rock, at the bottom of a deep sinkhole, and is made up of circular huts from the Bronze Age and rectangular ones perhaps readapted in Roman times. A trekking excursion in Tiscali is a must: you will tackle challenging routes both passing from the western side of Oliano and from the eastern side of Dorgali. Two hours for the climb, one hour for the visit and an hour and a half for the descent. The paths run alongside the mountain and the higher you climb, the more the view opens up over the valley.

From Oliena, a village famous for artisan crafts, olive oil and Nepente wine, other evocative itineraries reach the top of Mount Maccione, Scala Pradu, a ‘terrace’ looking out at the sharp outlines of the peaks of Mount Corrasi, and su Campu de Orgoi, a mountain plateau, where the view extends all the way to the Supramonte of Orgosolo, Urzulei and Baunei.

Henry Tunnel

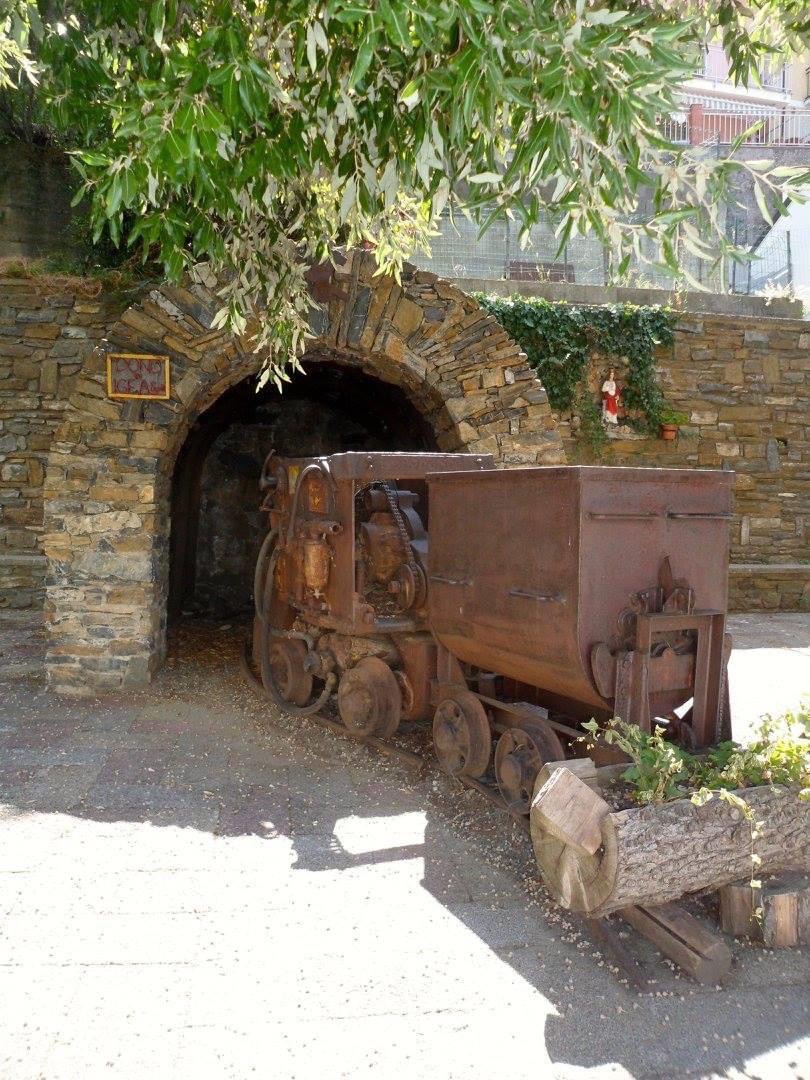

A labyrinth of tunnels carved into the rock, opening spectacularly onto sheer views of the island's south-west coast. The tour of the Henry tunnel, which has been made safe and can be visited with prior booking, is a journey through time inside the Pranu Sartu mine, Buggerru's most famous and productive mine. On the way out, you can take an electric train along the route of the old steam railway, and on the way back you can walk along the old 'pedestrian' tunnel, which was once used by pack mules. Walkways carved into the rock run the length of the cliff: some sections are in the dark, broken every now and then by the light coming from huge windows carved into the mountain face and overlooking the sea. The most spectacular view is at the end of the route: 50 metres above sea level, with a breathtaking backdrop overlooking the coast and the village's houses.

Excavation of the tunnel took place during the last three decades of the 19th century. For the time, this was a futuristic piece of engineering, as was the Porto Flavia tunnel. The remarkable size of the Henry - named after the French manager of the Anonime des Mines de Malfidano company, the concessionaire behind its exploitation, who decreed its construction - is due to the use, from the end of the 19th century, of a steam locomotive that ran through it and allowed the transport of raw minerals from the underground sites to the washeries and then to the port, where the cleaned minerals were loaded onto boats. Rail transport, on which the wagons of the coal-powered train ran, quickly replaced slow and costly transport on pack mules and was a huge step forward in the plant's productivity. At the time of the innovation, mining had been going on for thirty years, in 1865, with the transfer of the concessions to Anonime de Malfidano.

The exploitation of the site between the end of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century transformed a small village of farmers and fishermen into one of the main centres of the mining epic. The industrial 'revolution' was more sudden and abrupt than in other sites in Sulcis-Iglesiente. Today, thanks in part to the restoration of its industrial archaeology, Buggerru is one of the eight sites that make up Sardinia's UNESCO-recognised geo-mineral park, as well as an attractive resort boasting enchanting coastal landscapes, including the inimitable Cala Domestica and the beautiful town beach.

The tour of the 'Henry' is embellished by stories about mining life. The mines were places of suffering, where workers' solidarity and class consciousness flourished. In particular, Pranu Sartu is the symbol of the workers' struggle, the scene of the famous massacre at Buggerru in 1904.

The miners, exploited to the limit, 'dared' to stage a historic strike, the first in Italy's industrial history. In response, the mining company called in the army. The soldiers responded to the miners' stone pelting by opening fire: three workers died and eleven others were wounded. This episode led to other strikes throughout Italy. The trigger for the tragic uprising was the change in summer working hours, but the discontent was much deeper. Exploitation by French and Belgian bosses at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century was ruthless: gruelling shifts, no rest, the lowest wages in Europe, child labour, even having to pay for work tools, overtime to survive. As you enter the tunnel, you will notice a respectful silence, broken by the clanking of the wagons: in the dark and cold, you can imagine the atrocious things experienced by men of yesteryear who, with hard work and suffering, enabled their families to live a barely decent life.

Funtana Raminosa

A great page of history: here the Nuragic people extracted the essential component of bronze, which they melted down to shape statuettes, tools, jewellery and weapons. Funtana Raminosa, one of the richest copper deposits in Europe, is one of the eight areas that make up Sardinia’s geo-mineral park, listed among UNESCO’s Geoparks. It is an open-air and underground museum, which can be visited by booking, with working machinery that was state-of-the-art at the time and is still in excellent condition. The 'copper well' covers an area of about 150 square kilometres and is ten kilometres from Gadoni, a mountain village in the Barbagia di Belvì area, whose history, economy and identity it represents.

Since prehistoric times, it has been a key player in Mediterranean metallurgy, and after the Nuragics, the site was exploited by the Phoenicians and Carthaginians, then by the Romans: tools, an ingot and the remains of a miner dating from the Imperial age have been found. Two of the current 150 'tunnels', the Phoenician and Roman tunnels, date back to the ancient heritage. The area was perhaps also frequented by the Saracens in the 8th century, as confirmed by the name of the Saraxinus stream, a tributary of the Flumendosa, on the left bank of which, in a deep and lush valley, stands the mining plant.

The first person to start research for excavations and cultivation was the Spaniard Pietro Xinto, in 1517. The Roman tunnels were discovered by explorers at the end of the 19th century, while the 'real' industrial activity took place at the beginning of the 20th century. The modern 'Copper Age' saw Spanish, Belgian, French, Italian and even American companies playing a leading role throughout most of the century. In 1915 the concession was awarded to a French company, which made substantial investments to modernise the mining systems and build a mechanical washery, which became fully operational in 1920 with trials of the flotation system for processing mixed minerals. In 1936, the mine passed into the hands of the Società Anonima Funtana Raminosa, which helped create a mining village with a school, clinic, shop and a chapel dedicated to Santa Barbara. In the 1940s the complex was entrusted to 'Cogne', which built a one-kilometre cableway to transport the ore to Taccu Zippiri, followed by a second one in 1956, which further optimised transport. At that time 300 workers were employed at the plant, until the 1960s, when the mining crisis began. This led to the closure of many plants, including the coal mines in nearby Seui. Every effort was made to save the business, even building a thousand-ton-per-day mineral processing plant. It came into operation in 1982, worked for just eight months, and was the coup de grace: Funtana Raminosa closed in 1983. A group of 19 miners occupied the shafts, staying 400 metres underground for twenty days. The aim was to prevent the permanent closure or, alternatively, the conversion of the plants. Today, the former miners are guides to help you discover the mines, which were opened to the public in 2020: armed with helmets, you can listen to their stories and visit mining sites with ore processing plants, part of the 150 tunnels, open-cast excavations, the washery preserved as it was left on the last day of work, the cableway, small railway convoys, mechanical shovels, drills, a myriad of tools, time-scarred instruments to remind you of the hard work, and fragments of mining history that follow one another through the tunnels, as if time had stood still. The drops of water provide the soundtrack and the colours of the rock faces, from electric blue to pure white, provide the backdrop. Along the road towards the mine entrance you will see the village, with terraced housing and services, from offices to the canteen, from the church to the school, from the infirmary to the shop, all the way to the management building overlooking the facilities from a small hill.

All around, a fairy-tale setting, sculpted in time, intertwining superb nature and industrial architecture.

Conti Vecchi Saltworks

Amidst mountains glistening in the sun, the green of the Mediterranean maquis and pools as pink as the flamingos that nest there undisturbed, stands a model of industrial efficiency, where man and nature have lived in harmony for almost a century. The modern plants still in operation coexist with the memory told by the factories and machinery of the past, perfectly preserved and turned into a museum alongside the management offices furnished in Art Nouveau style and the buildings of the 'citadel of salt'. In these parts, work has never stopped since 1931: the Conti Vecchi Saltworks have withstood war and industrial crises and cover 2,700 hectares next to the Macchiareddu hub, set in the Santa Gilla lagoon, between Assemini, Capoterra and Cagliari. The oasis was redeveloped and opened to the public in 2017 thanks to a partnership between the Italian Environmental Fund (Fai) and Syndial-Eni. Within the factory, tours of the industrial archaeology site are accompanied by salt farming, which is unique in Italy.

It all began in 1921, when the Cagliari pond was a malarial swamp. The Florentine engineer Luigi Conti Vecchi, former director of the island's railways and a general returning to his beloved Sardinia from the Great War, was granted the concession for the area to reclaim the pond and set up a colossal saltworks, but the business was actually carried on by his family - first his son Guido, then his son-in-law and grandson. From an unhealthy area on the outskirts of Cagliari, a thriving, cutting-edge, eco-sustainable and self-sufficient industrial reality was born, employing over a thousand people and producing 250,000 tonnes of salt a year, which was also exported abroad. The ambitious project also gave rise to a township with an infirmary, church, shop, recreational and leisure facilities. Families of owners, managers and workers lived there together, their children went to the same kindergarten, even weddings were held in the saltworks and meals in the canteen were free. Each house had a bathroom - rare in those days -, a chicken coop and a vegetable garden. This is why the Conti Vecchi saltworks and village are a unique case in the island's working-class history. Nothing remains of the houses, built of ladiri (mud and straw bricks). The buildings that housed the owners and employees remain standing. A slow decline accompanied the changes of ownership in the 1970s. The turning point came in 1984 when the complex was taken over by Eni, which began the redevelopment process through Eni Rewind (formerly Syndial), later completed by Fai.

The two-hour tour includes a museum, industrial archaeology, modern plants and a bird sanctuary. The first part takes place in the historic premises, where time seems to have stood still: the management offices, workshop and chemical laboratory, where the women worked, have been restored to their original appearance, as they were in the 1930s, with machinery, tools and archive documents. The accounts department preserves typewriters and comptometers (the ancestors of calculators), records, registers and payrolls, while the technical department houses models for spare parts. The salt machine never stopped: until 2003, the missing parts were manufactured in the workshop, the 'heart and brain' of the saltworks. The voyage back in time is accompanied by fascinating video narratives: one in the former carpenter's workshop illustrates the salt cycle and natural aspects; a second in the workshop tells the story of the second largest saltworks in Italy. Outside the old halls, production - 400,000 tonnes a year - is revived through high-tech processes, destined for food, de-icing roads and detergent and cosmetics companies. The second part of the visit to the 'world of salt' is a seven-kilometre tour on a small train, accompanied by stories from the driver-guide. The itinerary winds its way through evaporation basins, salt flats, white salt piles and glasswort meadows. The flats are home to tens of thousands of water birds. The masters of the house, however, are the flamingos: their permanent colony comprises some ten thousand specimens.

Talmone military battery

It blends with the setting of granite rocks and Mediterranean scrub and is reflected in the clear blue waters, where it has been watching over the stretch of sea between the uncontaminated island of Spargi and Sardinia for two centuries. The Talmone military battery stands on Punta Don Diego, next to the beach of the same name and near Cala Trana, in the territory of Palau: it is an integral part of a defence system built at the end of the 18th century on the extreme northern coast of the Island, after the conquest of the Maddalena Archipelago by the Savoys. It consists of around fifty forts, small forts and batteries, scattered throughout the present-day national park. A place of great historical value, protagonist in events of war during the Unification of Italy and the world wars. The numerous guns that looked out from its underground battlements defended the borders of two kingdoms, Sardinia and Italy, becoming strategically important after the Unification of Italy, especially when the royal fleet took up residence in the Maddalena base.

From the watchtower of Talmone, the adjacent canal between the mainland and Spargi was kept in the line of fire and was the scene of epic naval battles during the Second World War. Then, in 1947, the Treaty of Paris compelled Italy to dismantle the base and discontinue the military batteries. More than half a century of abandonment followed, until 2002, when the maritime artillery site was entrusted under concession for 25 years by the Sardinia Region to the Fondo Ambiente Italiano - FAI (Italian National Trust), which, thanks to careful restyling and redevelopment interventions - still in progress - guarantees its opening and visits open to the public.

After parking your car in the locality of Costa Serena, you will come to the military fortification, by taking an easy albeit bumpy path towards Punta Sardegna, surrounded by greenery, with the scents of juniper, laurel and myrtle and granite sculptures carved by the northwesterly wind, and moving above beaches and marvellous coves. Your half-hour walk will be rewarded with the quietness of a former military shelter by the sea.

The naval battery, a sort of ‘ship on land’ perfectly located in the rugged and spectacular Gallura landscape, takes us back in time and tells us about military works and secrets, discreet traces left by man in uncontaminated nature, the hard life of soldiers and the long and solitary hours spent gazing at the sea. You will see the basement glacises where cannons were positioned, with the ammunition depots alongside them, then a turret that served as a gun laying station and lastly, about 70 metres from the shooting stations, the barracks, its numerous splendidly-restored rooms and original bright colours. Inside the dormitories that accommodated 70 sailors stationed at Punta Don Diego, were the guards’ quarters, the command office, the canteen and the caboose. At the top, on the right, there is an observatory. The armed batteries are on the sea, with a lookout equipped with machine guns, and in the vegetation you will see the armoury entirely dug out of the granite rock, while, beyond the battery, a coastal path reaches another lookout camouflaged between the granite rocks. In fact, the most evident feature is the perfect integration between the complex and the environment, in which it is totally camouflaged and hidden from the enemy.

S'Ortali 'e su Monti

Domus de Janas, menhir, megalithic circle, nuraghe, Tomb of Giants, village and granary: s’Ortali ‘e su monti, a stone's throw from the sea of Ogliastra, summarises three thousand years of prehistory, narrated by substantial pre-Nuragic findings (4th-3rd millennium BC) and by Nuragic monuments built between the Middle Bronze Age and the Early Iron Age (16th-9th century BC). The archaeological park stands on two adjacent hills in the locality of San Salvatore, about five kilometres from Tortolì: you can get to it by taking a detour along the road that leads from the town to the Lido di Orrì, also allowing you to reach the little church of San Salvatore.

The most ancient piece of evidence in the complex dates back to the Late Neolithic period (3500-2700 BC) and is a domus de Janas, part of the larger necropolis of Monte Terli. The little funeral cave consists of a short corridor and a large room in which there are five niches. It was carved out of the granite at least one, or maybe two, thousand years before the advent of the Nuragic people, who reused it. Right next to the domus, the complex-design nuraghe was built, alternatively called s’Ortali ‘e su monti or San Salvatore and was constructed with roughly-hewn granite blocks, unevenly placed on top of one another. The central tower (fortified tower), investigated in 2010, is of the tholos (false dome) type and ‘experienced’ lengthy use, most recently in historic times, as shown by the Roman and Byzantine burials. Today, the nuraghe is five and a half metres high, but evidence suggests that it originally reached a height of twenty-metres, making it taller than su Nuraxi in Barumini. It has a 15-metre diameter, the same as that of Santu Antine, the Nuragic palace of Torralba. You can enter the fortified tower via an entrance above which there is an architrave - a reused menhir - and a triangular window. The entrance leads into a corridor covered by skilfully crafted slabs. Leaving the large stairwell on your left, the passageway leads to a circular room, with three niches that form a cross. Around the tower, there is a boundary wall with an atypical irregularly elliptical design, which incorporates three secondary towers: the one to the north appears to be the best-preserved. Of the three original entrances, the one to the east is accessible and led into the courtyard in front of the fortified tower. Outside the bastion, you will notice several strictures leaning against the boundary wall and the remains of about ten huts: two with fireplaces where pottery and everyday objects were recovered. To the north, leaning against the curtain wall, you will see an area used for preserving foodstuffs, consisting of a floor where ten silos were located. In one of these, a significant quantity of wheat was recovered and an equal amount was contained in large jars inside the huts, almost all of which were equipped with millstones. One constituted a ‘mill hut’. So, there is little doubt about the main activity of the village’s inhabitants: harvesting, processing and storing of wheat, which required the intensive cultivation of the fertile plains at the foot of the nuraghe. Wheat was produced in quantities sufficient to be exchanged for other goods, forming the basis for trade: s’Ortali ‘e su Monti is the best example of a granary in Nuragic Sardinia. It is likely that the size of the settlement, estimated at one hundred huts, extended beyond the current archaeological park. On the part of the hill mostly facing the sea, you will see a space delimited by rocks positioned in a circle, with a diameter of almost twelve metres: this was not a random order. Here, the findings, which can be attributed to the culture of Monte Claro, confirm that the site was frequented during the Copper Age (2500-1800 BC). On the other hill, in the area where the Neolithic sacred area once stood, the Nuragic people installed a Tomb of Giants created using the row technique. Their typical burial place was built at the same time as the nuraghe, in the 15th century BC. The front is formed by slabs anchored into the ground to form a semicircle (exedra), while the lower part of an imposing centred stele with bas-relief crown moulding was placed in the centre, originally consisting of two or three blocks. Behind it, you can admire part of the apsidal body of the tomb, once over 15 metres long and ten metres wide. The walls are formed by embedded slabs with large granite blocks resting upon them. Most of these are reused menhirs, coming from nearby formations, made up of dozens of monoliths. Two of them are still standing next to the tomb, together with symbols of fertility and tombstones, the highest of which is nearly four metres tall.

Nuraghe Diana

The hills and coastline of Quartu Sant'Elena are home to 38 Nuragic settlements, the most beautiful of which is the Nuraghe Diana, dating from the middle of the 2nd millennium BC between the Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages and built to guard the Nuragic port. The Nuraghe Diana complex is unique, as the wall enclosing the inner courtyard was designed and built at the same time as the tower toppoed with a tholos false dome and the other two smaller connected towers. This modus operandi makes it unique among nuraghi that were expanded over time and only later were the other buildings annexed to the central tower. The construction technique is also an enigma, revealing unusual architectural and stylistic skills, a quest for beauty and a challenge to the laws of physics. In some places the upper stones are larger than the lower ones and the entrance follows the construction technique of a dolmen with a lintel and cyclopean sides, reminiscent of the entrance to the beautiful Giants' Tomb of is Concias in the countryside of Quartucciu. Excavations and tunnels can be seen around the nuraghe, not by archaeologists or grave robbers, but by treasure hunters looking for the treasure of the Saracen pirate Giacomo Mugahid, who was said to have buried it within these walls before leaving the island in the hope of returning to recover it and reunite with his wife. He never returned and it has never been known whether a treasure was actually found. However, the legend has survived, passed down through the grapevine, of the woman's spirit wandering within the walls of the nuraghe, guarding the hiding place and scanning the sea in the vain expectation of spotting the privateer's sailing ship on the waters of the Golfo degli Angeli (‘Gulf of Angels’). In memory of his love, the beach overlooked by the nuraghe was named Capitana.

The Diana is not only the inspiration for legends of pirates and treasure, but also a witness to bloody battles between privateers. The promontory at its foot is perhaps not by chance called is Mortorius, a sinister name in spite of its beauty. The thousands of years of history, of which the Nuraghe Diana can rightly boast, extend as far as the modern era. During the Second World War, it was once again a sentry on the sea, this time protecting the forts protecting against sea and air attacks camouflaged in the ruins of an old tuna fishery. At that time only the main tower of the nuraghe emerged from the hill, which was reinforced to build a sentry box. In the 1950s, after the end of the war, excavations began that brought to light a trilobate nuragic complex with a unique architecture created by the ancient architects, which the touch of modern history has not altered.